The Metamorphosis of the New Orleans Baby Doll Tradition

The New Orleans Baby Doll tradition is one of the city’s most fascinating cultural practices, blending music, dance, costuming, and community spirit.

Born in the early 20th century as part of the city’s jazz movement, the Baby Doll masquerade became a bold form of expression for women in African American communities.

By the 1920s, the tradition had spread beyond its early roots in Back o’ Town and Storyville, gaining traction within families and social aid clubs across the city. Over the decades, the practice evolved, declined, and eventually reemerged through modern revivals. This cultural journey can be understood as a metamorphosis, a transformation that reflects both resilience and change.

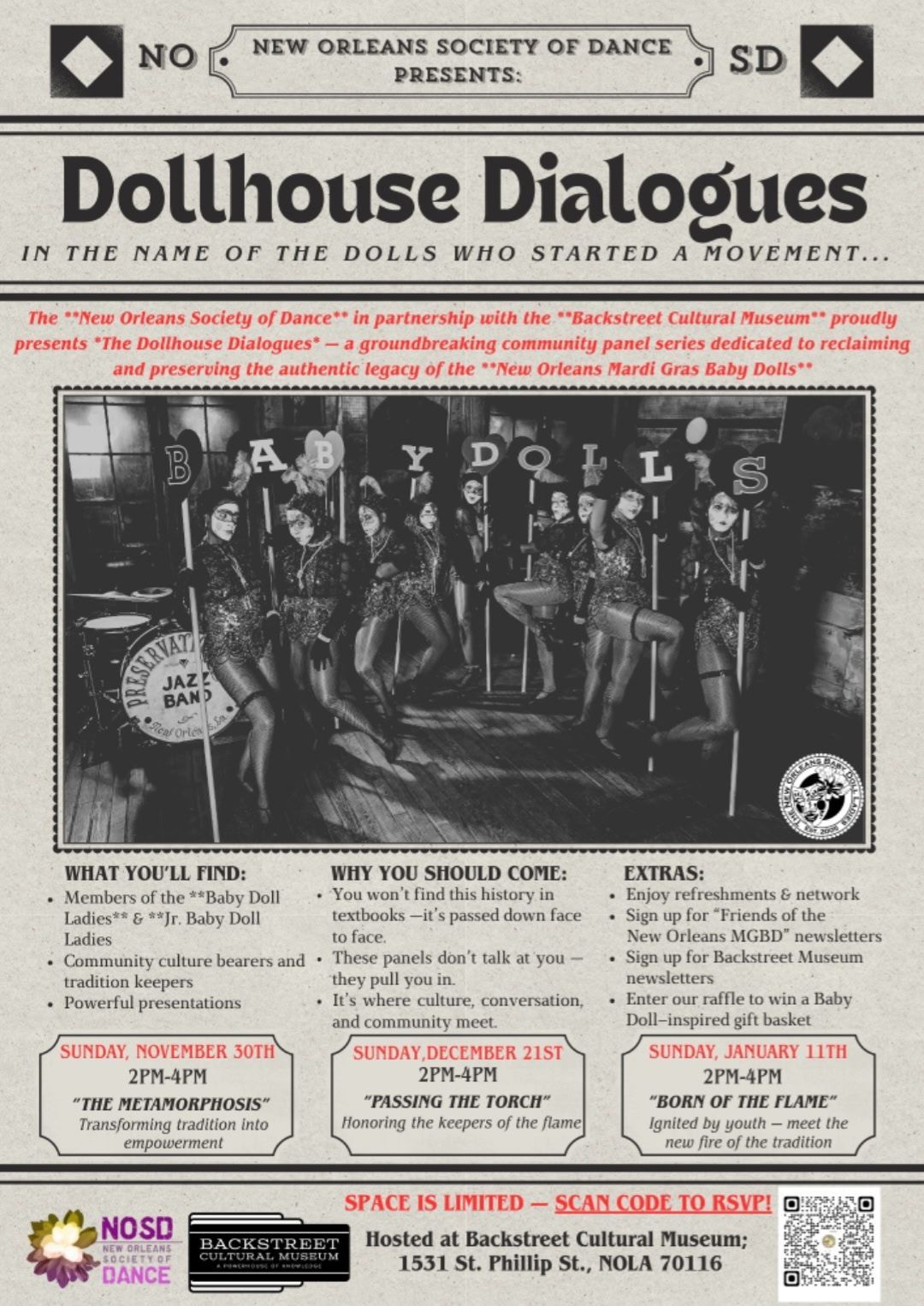

Today, groups such as the New Orleans Society of Dance continue to honor and preserve this unique tradition, keeping it alive for future generations.

The Spread of Doll Masquerading

Social Aid and Pleasure Clubs

During the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s, social aid and pleasure clubs became an important force in maintaining and expanding the Baby Doll tradition. These organizations were more than social groups, they were lifelines for African American communities, providing insurance, burial assistance, and spaces for cultural expression.

Baby Doll masquerading became part of Mardi Gras celebrations as well as other holidays, such as St. Joseph’s Night. Members dressed in elaborate doll costumes, complete with wigs, bonnets, and flouncy dresses, parading through the streets to the sound of live music.

Family Groups and Neighborhoods

In addition to formal clubs, many families adopted the Baby Doll tradition as their own. Costuming, dancing, and parading were passed down through generations, ensuring that the practice remained woven into the fabric of community life.

The Golden Slipper Social Club

Origins and Legacy

One of the most influential Baby Doll groups in New Orleans history was the Golden Slipper Social Club, formed around 1930 by Alma Trepagnier-Batiste. Alma came from a family of musicians, including members of the former Dirty Dozen Kazoo Band, and together they created one of the longest-running Baby Doll groups.

For fifty years spanning from the 1930s through the 1980s the Golden Slipper Baby Dolls paraded during Mardi Gras and other celebrations. Their longevity helped cement the Baby Doll masquerade as a recognizable and respected part of New Orleans culture.

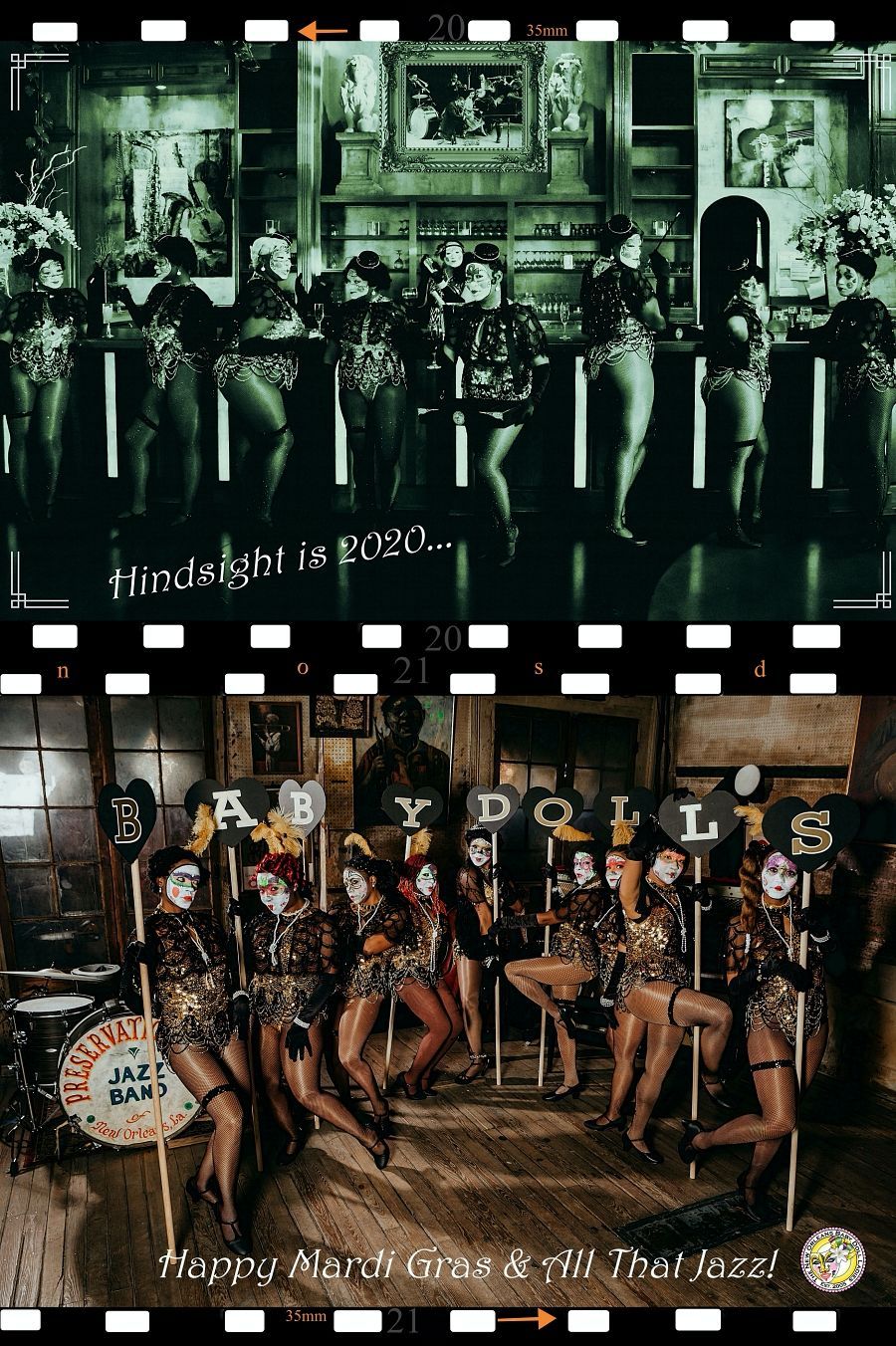

Costuming and Performance

The Golden Slipper Dolls’ traditions highlight the dual nature of Baby Doll performance. In the morning, they would appear in full, doll-like attire, with curly wigs, bonnets, and modest dresses that imitated toy figurines.

By the afternoon, the women transformed into a bolder version of the Baby Doll persona. They switched into shorter, satin dresses, paired with stockings and garters, and performed provocative dances to entertain crowds. This transformation emphasized both playfulness and defiance, blurring the boundaries between performance and social commentary.

Community Celebrations

Their parades were not limited to public streets. After performing, the group often gathered at a relative’s home where food and music awaited them. These gatherings reinforced the role of the Baby Doll tradition as both a cultural performance and a family-centered celebration.

The Decline of Baby Doll Groups

Cultural Shifts by the 1980s

By the 1980s, the once-vibrant tradition of neighborhood Baby Doll groups had entered a period of decline. Many of the original performers had aged, and the widespread, en masse practice of doll masquerading decreased dramatically.

Urban development, shifts in community structures, and changes in Mardi Gras traditions all contributed to the decline. Without younger generations stepping in to carry on the practice, the tradition risked disappearing altogether.

Dormancy of the Tradition

For several years, the Baby Doll masquerade remained largely dormant, remembered mostly through oral histories, archival photos, and the memories of those who had seen the Golden Slipper and similar groups perform.

Revival Efforts in the 21st Century

Antoinette K-Doe and the Ernie K-Doe Baby Dolls

The early 2000s saw a brief but meaningful revival of the Baby Doll tradition. Antoinette K-Doe, wife of the legendary R&B musician Ernie K-Doe, co-founded the Ernie-K-Doe Baby Dolls around 2003.

Alongside Geannie Thomas and “Tee Eva” Perry, Antoinette K-Doe worked under the mentorship of Miriam Batiste-Reed, daughter of Alma Trepagnier-Batiste. Miriam had been deeply connected to the Golden Slipper Social Club and brought her first-hand knowledge of the tradition into this revival effort.

A New Purpose

The Ernie K-Doe Baby Dolls honored the classic costumes of earlier generations but also expanded the mission of the group. They sought to blend Mardi Gras tradition with civic responsibility, spearheading initiatives that supported the community.

Their efforts included:

- Feeding the hungry

- Providing funerals for the deceased

- Fundraising for local musicians in need

Through these actions, the group demonstrated how cultural practices could evolve into vehicles for community activism while maintaining their artistic integrity.

Performances and Public Life

The Ernie K-Doe Baby Dolls were both singers and dancers, masking in traditional Baby Doll style while performing on stages across New Orleans. Their work brought visibility to the tradition at a time when it risked fading into obscurity. Although the group only lasted a few years (2003–2005), it left a lasting mark on the cultural landscape.

The Living Tradition: The New Orleans Society of Dance

Carrying the Legacy Forward

While earlier revivals kept the Baby Doll practice alive, the New Orleans Society of Dance has taken on a long-term role in preserving and celebrating this cultural heritage. Founded and directed by Milllisia White, the Society connects historical Baby Doll traditions with contemporary performance and education.

The group not only performs but also serves as a steward of cultural history, ensuring that the Baby Doll legacy continues to inspire future generations.

Cultural Education and Preservation

The New Orleans Society of Dance emphasizes the importance of teaching the origins and cultural significance of the Baby Doll tradition. Through dance, costuming, and storytelling, the group educates audiences about how these traditions emerged from jazz culture and evolved over time.

Modern Performances

In parades, festivals, and stage productions, the Baby Doll Ladies of the New Orleans Society of Dance showcase the artistry, resilience, and creativity that have always defined this tradition. Their performances are not replicas of the past but living interpretations, proving that culture thrives through adaptation as well as preservation.

Why the Metamorphosis Matters

The Baby Doll tradition’s journey from its rise in the 1920s, to its height under the Golden Slipper Club, to its decline and eventual revival demonstrates the resilience of New Orleans culture.

It is a reminder that traditions are not static. They shift, adapt, and sometimes disappear, only to reemerge in new forms. The Baby Doll masquerade reflects the creativity and perseverance of African American women who used costume, dance, and music to assert identity and celebrate community.

The metamorphosis of this tradition ensures that the voices and artistry of these women are not forgotten. Instead, they continue to inspire new generations of performers, educators, and cultural leaders.

Conclusion

The story of the Baby Doll tradition in New Orleans is one of transformation, resilience, and revival. From the Golden Slipper Social Club’s fifty-year reign to the short-lived but impactful Ernie K-Doe Baby Dolls, the practice has continually adapted to changing times.

Today, the New Orleans Society of Dance stands as a living link to this cultural heritage. By honoring the legacy of past Baby Doll groups while engaging with contemporary audiences, the Society ensures that this uniquely New Orleans tradition will continue to evolve and inspire.

To learn more about the Baby Doll Ladies and their cultural contributions, visit the New Orleans Society of Dance.